Last year (2022) marked the centenary of the first publication of possibly the greatest poem of the 20th Century: T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. My photobook Unreal City is a kind of photographic conversation with Eliot’s masterpiece, with London as the key focus (in Eliot’s poem, London is the “Unreal City”). The book was printed just before the Covid pandemic started, and so marks an interesting turning point in the history of the city. Below is an extract from the Introduction to the book, which I wrote in 2019.

London is many things to many people. To those for whom money is no object it can be a 24/7 narcotics-fuelled party; an opportunity to indulge in every luxury dreamt up by man and woman; a cultural paradise of galleries, theatres, refined music, Michelin-starred dining, exclusive public schools and private members clubs. London is home to the greatest number of billionaires on the planet and has the only shop in the world where those with enough money can walk in off the street and buy a private jet.

But to those who are not so fortunate it can be a squalid and dangerous place where one’s person is constantly in harm’s way; where one is at risk of knife crime, acid attacks and gun violence; where one does one’s best to eke out an existence doing menial jobs on zero hours contracts; where one’s children might easily slip through the fingers of failing schools and into the waiting arms of violent gangs. In 2018, 135 people were murdered or unlawfully killed in London: the highest total since 2008. Many of the victims were teenagers or in their twenties, and most were stabbed. In February and March 2018 London edged New York City in the number of homicides committed for the first time in modern history.

Subsequent to starting this project I discovered an excellent collection of essays entitled Tales of Two Londons: Stories From a Fractured City (edited by Claire Armitstead), which I can wholeheartedly recommend. In one essay Lynsey Hanley writes of living on a council estate in East London: “Although we loved our flat, the estate as a whole was poorly designed and had been left to decline. It felt like a wasteland.” Hanley’s experience chimes with that of many others in the Two Londons volume, not to mention with articles in the press that report incidents of racism, discrimination, violence and waste (in a multitude of forms) that occur in London on a daily basis.

To its poorest residents, London at its worst is a land of waste (dirty streets, fly tipping and uncollected rubbish); of lives lost to gangs, racial hatred, crime, untreated physical and mental health issues; where a lack of opportunities means that you are unable to improve your physical, material, psychological and emotional well-being, or to contribute to society in a meaningful way.

From the perspective of many very wealthy individuals, the poor are seen – if they are seen at all – as enablers of their own lifestyles, or as an inconvenience: a blot on the landscape. Illustrating the first point, Patrick Colquhoun, a beneficiary of the family silver spoon, commented in 1806 that:

Poverty … is a most necessary and indispensable ingredient in society, without which nations and communities could not exist in a state of civilisation. It is the lot of man – it is the source of wealth, since without poverty there would be no labour, and without labour there could be no riches, no refinement, no comfort, and no benefit to those who may be possessed of wealth.

One wonders if Mr Colquhoun would have been quite so sanguine about the forces of inequality if he himself had been condemned to a life of serfdom (in an Amazon fulfilment centre, perhaps, or the “dark satanic mills” of JD Sports or Asos).

The second point was tragically demonstrated at Grenfell Tower where, according to survivors of the fire, the flammable cladding was put on to make the building appear more aesthetically pleasing to its wealthy neighbours. The first epigraph of the book highlights the discrepancy between the lip service paid to equality by those in power, and the cruel reality of growing inequality experienced by those who find it difficult or impossible to make ends meet (most recently as the result of a decade of brutal Tory austerity and increasingly unaffordable housing). As poorer individuals, families and communities are gradually displaced to make room for the internationally mobile elite (whose expensive properties often remain empty for most of the year), the consequent hollowing out of London only adds to the wasteland effect.

While such concerns have an inherent political urgency, they acquire added resonances when viewed in the context of The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot’s modernist poetic masterpiece, hailed by many as the greatest poem of the 20th century. The project of this book is to frame some of London’s harsher realities in terms of a visual response to, and a conversation with, Eliot’s text, although I would have to qualify this by saying that it is my own creative transmutation of The Waste Land which forms the basis of the juxtaposition, and not an attempt to determine what Eliot’s own visual take might have been.

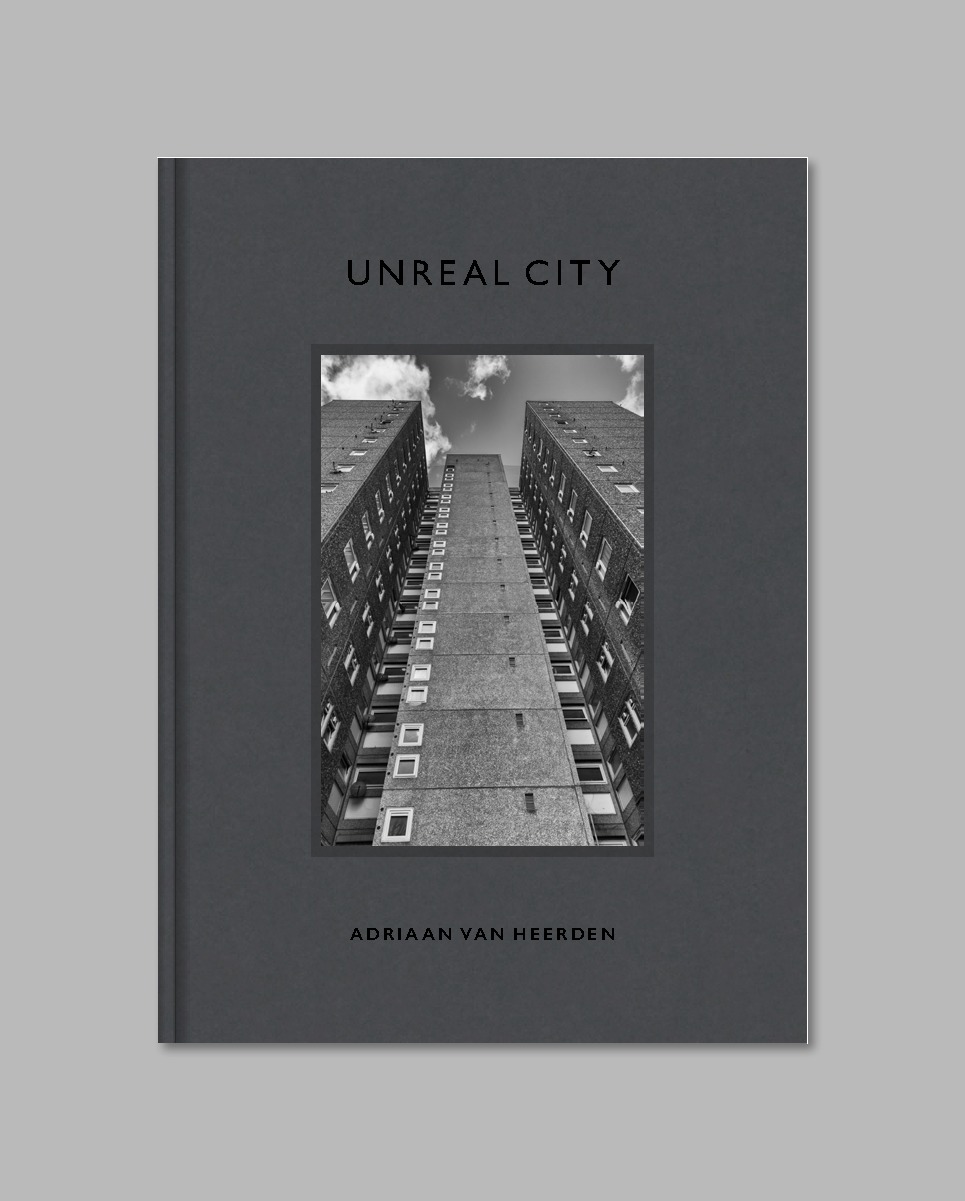

Inspired to some extent by the Elmet Project (a collaboration between the poet Ted Hughes and the photographer Fay Godwin), the 85 photographs in Unreal City present London through the lens of The Waste Land. London was of course the dominant landscape in Eliot’s poem, the “Unreal City” on which its camera has come to focus by the beginning of the last stanza of Part 1, and in which many of the poem’s characters have their (abrupt) exits and entrances.

Unreal City reflects many of the poem’s major themes: a strong sense of alienation; people’s failure to connect meaningfully with one another; the way in which the machinery of high capitalism grinds up souls, leaving behind only husks of humanity; the failure of religion to provide comfort in this broken world; and the apparently unbridgeable divide between rich and poor.

It is worth reiterating that the pictures in this book are not a straightforward illustration of the text of the poem, as the photographs in the Elmet Project perhaps are. In the process of giving expression to the ideas mentioned above, the pictures started creating a language (a “system of signs”) of their own, and certain visual motifs were created in the pictures which are not present in the text of the poem. The “towers of the rich versus towers of the poor” motif, for example, arguably hinges the book into a more radical political stance than that occupied by Eliot’s poem. This pivoting motion opens up new lines of conversation. Throughout the book my aim has been to draw the reader into a dialogue between text and image, in which each enriches and illuminates the other.

The second epigraph I chose for Unreal City is the one that Eliot originally intended for the poem (before Ezra Pound intervened): a quotation from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in which the narrator, Marlow, reports on the death of Kurtz. As the reinstated epigraph suggests, the pictures contained in Unreal City are connected by the understanding that the waste land is not (only) created by tragic forces beyond our control, but (also) by our own particular, postmillennial darkness. This “darkness” is characterised by the fact that, in spite of living in what is supposedly the age of connectivity, we are as alienated from others as ever due to our frequent failure to communicate in ways that transcend the ephemeral and the banal; our inability to exhibit empathy and compassion, and to alleviate suffering in a lasting and holistic way.

According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, “unreal” has a double meaning: “as if imagined; strange and dream-like”, and a slang version: “extremely or surprisingly good.” Whether London can reverse its descent into “unreality” (in the first sense) and become a surprisingly good place to live in for all its inhabitants remains to be seen. The dark humour which is evident in several of the pictures emphasizes the “unreality” of life in the capital, but also holds out a few rays of hope that all may not be lost.